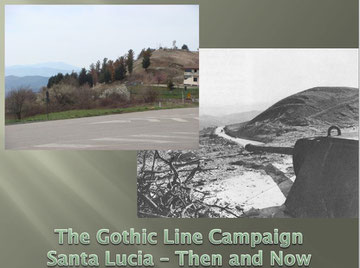

The Italian Campaign and the Gothic Line 1943-1945

The bloody and prolonged fight between Allied and Axis troops from Sicily up the “Boot” until to the Brenner pass (10 July 1943 - 2 May 1945) was not the logical outcome of a clear war strategy. It was a compromise between conflicting views by the US and the British, as well as a result of German uncertainties on their Mediterranean strategy.

Futa Pass and Il Giogo Pass Campaign

The last major line of defense in the final stages of World War II,

along the Apennines formed by Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, was named “Gothic Line" (Gotenstellung). During the Summer of 1944, when it was feared the Allied armies would easily breach it and

fan out in the Po Valley after their advance North of Rome, the name was changed by Kesselring to “Green Line” (Grüne Linie), so as not to compromise such an imposing denomination, but the first

name survived in general parlance.

The tactics of retreating to organized lines of defense prepared along prominent terrain features up the Italian “boot” (such as the "Gustav Line" at Cassino) was successfully followed by the

German Army throughout the Italian Campaign. The German command had started to study the idea of fortifying the Central Apennines already in August 1943, when the Allies were still fighting in

Sicily. Work however started only during the Spring of 1944, under the direction of the Todt work organization.

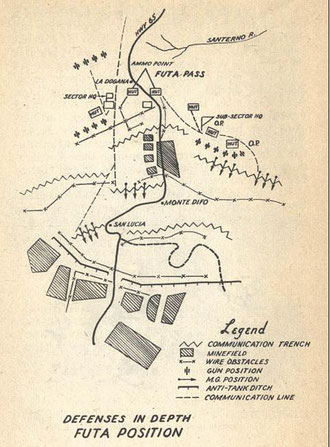

The Gothic Line was not a continuous line of fortification, but rather a series of strong-points arranged in depth, exploiting the natural terrain features which favored the defender. Traversing the Italian mainland from the Tyrrhenian coast North of Viareggio to the Adriatic at Pesaro, the line extended for more than 300 km. It included thousands of field fortifications made of wood, rock or steel-girded concrete, and included long antitank ditches such as the one at Santa Lucia near the Futa Pass. Extended mine fields and wire emplacements completed the picture.

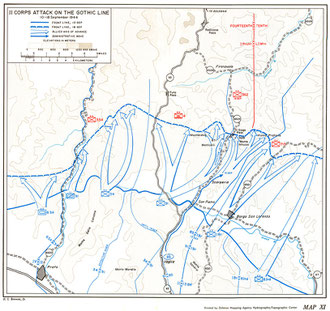

Luckily for the Allies, construction work was still incomplete when the advancing armies approached the Central Apennines. Both coastlines, being more vulnerable, had received priority and were better defended. Due to terrain features, the weakest points in the line were the Futa Pass and the Adriatic coast. These areas were therefore the most heavily defended. At the Futa Pass the Germans placed two of the five divisions defending the whole Apennines sector. Apart from the 5-km long antitank ditch, routes of attack were covered by concrete pillboxes and Panther tank turrets with 75 mm guns. The advance line of resistance was usually anchored on strong-points covered by extended wire and mine fields. Because of the enemy disposition, the US command decided to attempt a breakthrough at the less defended Giogo Pass, feinting a covering attack in force against the Futa Pass by the 34th and 91st Infantry Divisions.

A penetration through the Giogo Pass could be expected to outflank the enemy strength at the Futa Pass. It was recognized that any successful attack against the Giogo Pass would require capture of the dominant terrain features on either side of Highway 6524: the Monticelli hill mass on the west (left) and Monte Altuzzo on the east (right).

The 362nd Infantry Regiment Attack the Futa Pass (10 – 21 September 1944)

During the month of September the 91st Division fought its most brilliant campaign, in which it smashed the most formidable defensive positions in Italy, the Gothic Line. It advanced through elaborately constructed fortifications over mountainous terrain made hazardous by rain and fog, with unflinching determination and unwearying courage. According to one infantryman the climactic days, 12-22 September, were a "lifetime of mud, rain, sweat, strain, fear, courage, and prayers.” But with brilliant leadership and magnificent courage, the 91st Division cracked the Gothic Line and established itself as one of the great fighting Divisions of World War II.

The 91st Division moved into position during the night of 9 September. The 362nd Infantry relieved the 2nd Brigade of the 1st British Division near Vaglia. The attack was launched Sept. 10, 1944.

While the 363rd Infantry was battling for Monticelli (Giogo Pass area) on the left and the 361st Infantry fought for Hill 844 and 856, the 362nd Infantry was advancing up Highway 65 toward M. Calvi and Futa Pass. As in the other two sectors, the fighting was very bitter and the advance painfully slow, 13-15 September. With unwearying courage the Regiment fought its way from pillbox to pillbox, through barbed wire and minefields, always through areas in which the enemy had excellent observation and prepared fields of fire. On 14 September the 2nd Battalion occupied Mt. Calvi but could not exploit its position because of the terrific mortar concentrations which fell from Hills 821 and 840. Nor could the Battalion advance rapidly to Hill 840, for although the forward slope of Mt. Calvi is a gentle incline, the reverse slope drops abruptly to the foot of Hill 840, at some points as much as 500 feet in 200 yards. Not only was it almost impossible terrain for the infantry to cross, but artillery fire is masked in many areas. Thus even high angle fire was unable to reach the mole-like Germans dug in below.

Shortly after noon 15 September the 1st Battalion attacked north to Morcoiano according to a plan which involved nine TOT's being delivered by the massed artillery in 15 minutes. Progress of this attack was slow but steady. Morcoiano was heavily defended, but on 18 September the town fell and the Battalion pressed on. The next morning under a "nearly perfect" rolling barrage fired by the 346th Field Artillery the assault" on Poggio began. The artillery fire did not smash the fortifications, but it forced the defenders to seek cover and "button up" completely. Then when the fire moved past a given point, before the enemy could jump out of holes to man their weapons, the infantry, just a scant 300 yards behind the barrage, was upon them. Two hundred prisoners were taken. In this way the attack literally walked through a strong point that would ordinarily have been a scene of bloody and prolonged fighting.

On the same day, 19 September, the 2nd Battalion, attacking from the southeast, captured both Hill 821 and Hill 840. Advancing rapidly to keep contact with the enemy, now driven from his Main Line of Resistance, the Battalion occupied Mt. Alto during the night of 19-20 September.

Although the collapse of the enemy lines in the 362nd sector was not so spectacular as it was in the 361st sector, Hill 896 was captured the next day, and by the morning of 21 September Company A had reached the Santerno and had set up machine guns trained on Futa Pass.

The German Defense at Santa Lucia and Panna

In the meantime the 3rd Battalion, 362nd Infantry, which had been operating almost alone, with the closest unit more than 1000 yards away, was battling north along Highway 65. Despite a warning by General Livesay that it was not to try "to win the war by itself" it was trying to do exactly that. On the morning of 16 September the Battalion had come against a spectacular Anti-tank ditch over a mile long over hill and valley and covered by interlocking fields of machine gun fire. Covering the highway was the much-feared emplaced Panther turret with its 75mm tank mounted in a concrete emplacement, as well as other concrete pillboxes and dugouts commanding the approaches to the Pass.

For two consecutive days the Commanding Officer of the 3rd Battalion, directed the 346th Field Artillery in a steady pounding of Santa Lucia. The Panther turret tank gun was knocked out and two 105mm SP guns were destroyed. Every time the enemy attempted to move, the artillery hit him. On 20 September under a rolling barrage the Battalion attacked along the ridges, surprised the enemy, overran his positions, and captured Hill 689. The next day in a pincers movement they seized Santa Lucia and, under artillery fire which was seldom more than 300 yards ahead of the front-line troops, they took Hill 901. That night they outposted in Futa Pass in preparation for the final all-out assault against Hill 952, which commanded the vaunted Futa Pass defense system.

The next day, 21 September, the Battalion inched its way relentlessly up the hill against every type of fire the enemy could pour on it. Yet by nightfall it took positions on the summit. This was the culmination of the Division's 12 day battle to crack the Gothic Line. With the fall of Futa Pass, the door which had been unlocked at Monticelli and swung open by the drives of the 363rd and 361st Infantries literally fell off its hinge. The Gothic Line had been smashed.

Much of the credit for breaching the Gothic Line goes to the Division Artillery, composed of the 916, 346, 347, and 348 Field Artillery Battalions, augmented by the power of II Corps artillery. For preparations fired during the campaign the Division controlled 168 guns. During the period from 11 September to 22 September, inclusive, 94,379 rounds were fired, and during a single twenty-four hour period, 15 September, 14,321 rounds were fired.

The Panna Bunker

This Bunker was on the far end of the Santa Lucia defense line which also contained an anti tank ditch. We were not able to locate some remains of the ditch, but the bunker is still in good shape. It has been hit by a very heavy US artillery shell, as we found a shrapnel inside the casemate. We do not know if the Bunker was for an 105mm artillery gun or a Pak 40 – 75mm anti tank gun.

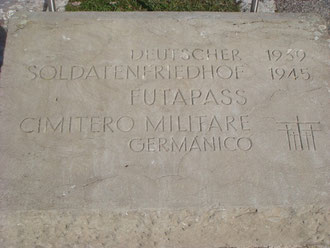

The German Cemetery on Futa Pass

After the heavy defense battle, the Apennines-Defense fell on April 21, 1945.

Most of the soldiers buried here have been killed during those battle. With 30’683 K.I.A’s the Futa Pass cemetery is the biggest one in Italy. The cemetery was officially opened on June 28, 1969.

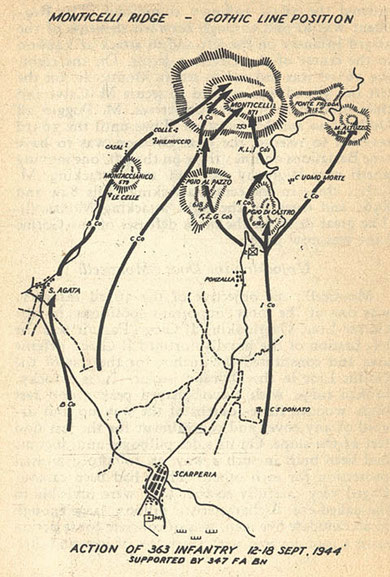

The US attack on the Giogo Pass (12 - 18 September 1944)

American Plans

The order of attack against the Giogo pass envisaged a maneuver aimed at conquering the heights overlooking highway 6524 (today SS 503) - the Monticelli hill mass to the West (91st ID sector) and Monte Altuzzo to the East (85th ID sector). Attacking units were supported by the entire Artillery complement of the II Corps. The attack was to be preceded by massive air strikes that would hit deep behind enemy lines and then shift to the front area.

Such big numbers notwithstanding (the US 5th Army at the time fielded ten combat divisions with a force of 262’000 men), the decisive battles on the front lines were fought by units totaling less than a thousand men: a few rifle companies belonging to a few Infantry battalions. On the German side, this disproportion was even more marked. The 4th Fallschirmjaeger Division alone, well below its full complement of troops and equipment, held a 20-kilometer front from the Futa Pass to Monte Pratone, with no available reserves. Among its men, only a few scattered veterans of the Cassino battles survived. Most were inexperienced replacements sent directly from Germany. Many had never fired their rifles.

German Positions

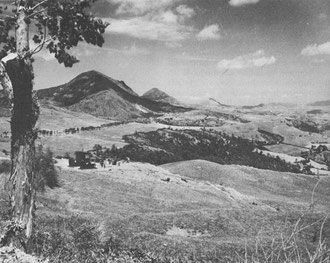

The German defense of the Giogo Pass sector of the Gothic Line was based on a group of 3,000-foot peaks, including. Monte Altuzzo and Monticelli, which flanked either side of the pass.

The only possible route for an Allied armored attack against the Giogo Pass was the main road, Highway 6524, which was narrow, full of sharp turns, and flanked by the bare slopes of Monticelli and by Monte Altuzzo. Since antitank weapons could easily bring effective fire on the highway, enemy engineers had devoted most of their efforts to developing strong infantry positions and had constructed heavy pillboxes and bunkers on the adjacent mountains.

The German Main Line of Resitance (MLR) on Monticelli included

concrete-reinforced dugouts blasted into the rock and larger shelters dug deep into the ground. Forward positions along the ridge line were protected by wire fields 100-yd deep. The only natural

approaches, two deep draws up the ridge, were heavily mined. On the reverse slope of Monticelli elaborate dugouts had been constructed by the Todt work organisation. These had

been dug straight back into the mountain to a distance of seventy-five feet and were large enough to accommodate twenty men. On a hill 300 yards north of Monticelli a huge dugout had been blasted

out of solid rock. Shaped like a U and equipped with cooking and sleeping quarters, it was large enough to accommodate 50 men. The Outpost Line of resistance covered the highway at

l'Omomorto.

On Monte Altuzzo, the German MLR developed along a trail at mid ridge covering the southern “bowl” of the mountain, anchored to the West on a crest which projected southward dominating the highway. To the East, the German defenses went up the ridge culminating at the top on hill 926, the highest point on Monte Altuzzo. The OPL covered approach routes along the western ridge and the main, eastern ridge line at hill 782.

Despite the shortage of front-line troops and reserves, the enemy intended to hold the Gothic Line as long as his limited resources would permit. On 8 September each soldier in Fallschirmjaeger Regiment 12, had received orders that "... the position is to be held to the last man and the last bullet even if the enemy breaks through on all sides as well as against strongest artillery or mortar fire. Only on authority of the company commander may the position be abandoned."

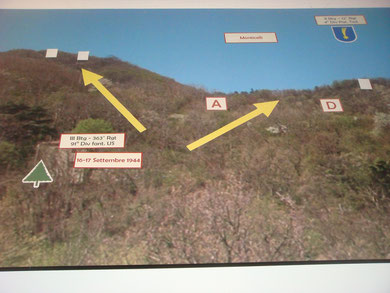

Unlocking the Door - The Attack on Monticelli by the 363rd Infantry Regiment (12 - 18 September 1944)

Monticelli, was one of the most important positions in the Gothic Line. Overlooking Il Giogo Pass, it was the left bastion of the heavily fortified Il Giogo defense area and constituted the anchor for the rest of the Gothic Line in the Division sector. It is a rocky, broken ridge, with a cone-shaped peak 3,000 feet high, wooded three-fourths of the way up, but devoid of any cover and concealment for the last 600 feet of the slope. On its sides pillboxes and dugouts had been built in such a way as to afford mutual protection for each other. These had been camouflaged very carefully so that they were invisible to the naked eye.

The command of the 363rd Infantry Regiment of the 91st Infantry Division estimated to be able to conquer both the Monticelli and Altuzzo hill-masses without help from the 85th Infantry Division. However, enemy resistance proved stronger than expected. Heavy and well-aimed concentrations of mortar and MG-fire, as well as night counterattacks by determined Fallschirmjaeger units prevented any advance. Uncertainty on the location of attacking units impeded the use of supporting Artillery fire.

On 13 September the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 363rd Infantry began the slow torturous attack. Each pillbox had to be knocked out individually by artillery or by flanking assaults by the infantry with hand grenades. Frequently minefields or wire obstacles had to be breached before the pillbox itself could be reduced. It was slow, bloody, costly fighting. In the afternoon the 2nd Battalion attacked between the 1st and 3rd Battalions and pushed under cover of a smoke screen to within 600 yards of the crest of Monticelli. The next morning, however, they were subjected to a heavy counterattack and driven from their positions.

After two days of slow progress the first break in the enemy defenses developed when front-line units succeeded in directing Artillery fire on top of the German positions. Company B, 363rd Infantry overran the enemy Main Line of Resistance during the late afternoon of September 15 and occupied the ridge line extending west from the peak of Monticelli. However, only 70 soldiers were left of its original strength of 200. Although B Company was isolated, out of supply and subjected to counterattack after counterattack and unrelenting artillery and mortar concentrations for two days, the flank was never turned (till the advance of the 3rd Battalion on the right wing of the attack reached hill 781 at the top of Monticelli on Sept. 17). After one counterattack two enemy were found sleeping in Company B foxholes!

The next day while the 1st Battalion held the left flank and

the 2nd Battalion maneuvered to reduce pillboxes that had held up its advance, the 3rd Battalion launched an attack on the peak. Despite every effort the intense mortar and machine gun fire

stopped the assault, and it finally bogged down.

On the morning of 17th September General Livesay, on the ground, laid the plans and personally supervised the preparations for the final assault. Every resource was marshaled for the effort. With

every Battalion exerting maximum pressure on the enemy, the 2nd Battalion, with Company K, made an all-out assault on the peak.

By 1330 Company K had advanced over a mile and had come to within 300 yards of the crest. At 1400 a rolling barrage in which 272 rounds of 105 mm were fired by the 347th Field Artillery in 25 minutes moved up the south- western slope of the mountain with the infantrymen following as close as 50 yards behind it. At 1448 word was received that the company commander of Company K, Captain William B. Fulton, his radio operator, and six enlisted men had reached the top of Monticelli.

In the Company B sector alone, more than 150 German K.I.A's were found after the fight, and 40 prisoners had been taken, at the cost of 14 dead and 126 wounded GIs. Other companies fared even worse – a wasteful, useless frontal attack by one Company in the 3rd Battalion substantially annihilated the unit as a fighting force within a few minutes with no gains accomplished.

In the Company B sector alone, more than 150 German K.I.A's were found after the fight, and 40 prisoners had been taken, at the cost of 14 dead and 126 wounded GIs. Other companies fared even worse – a wasteful, useless frontal attack by one Company in the 3rd Battalion substantially annihilated the unit as a fighting force within a few minutes with no gains accomplished.

Immediately the enemy laid an intense artillery and mortar concentration on the position and began to organize a counterattack of 200 to 300 men at a point 400 yards to the north. The company commander directed artillery fire on the area, and 46 rounds were fired in 45 minutes to break up the attack before it could get under way. Meanwhile the small band was reinforced, and at 172240 Col. Magill reported that "the situation is well in hand." During the night two Batteries of the 347th Field Artillery laid a ring of steel around Monticelli firing 4,000 rounds, a volley every three minutes. There was no counterattack; by morning, 18 September, Monticelli was occupied in strength.

Monticelli had been won by the courage and sacrifice of the 363rd Infantry and the superb support of the 347th Field Artillery and its associated units. The artillery pounded constantly at enemy positions. In one area where artillery fire had been directed for four days, 150 dead were later counted. One of the targets fired during the all-night barrage, 17-18 September proved to be a Battalion Command Post 30 feet wide dug 100 yards into the side of the mountain. The next day 33 prisoners were taken from the cave, dazed and shaken by the pounding they had received. The artillery had run the enemy into their holes, and the infantry had dug them out, and Monticelli fell.

General Keyes, Commanding General, II Corps, expressed his pride in the capture of the key position, the first break in the Gothic Line in the II Corps sector, when he telegraphed to General Livesay:

"Congratulations upon the capture of Monticelli. The successful accomplishment of this tough assignment is fitting tribute to the dogged determination and courage of the 91st."

The Attack on Monte Altuzzo (12 - 18 September 1944)

At approximately 0915, 12 September, Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark, Fifth Army

commander, and General Keyes stopped at the 338th Infantry command post and talked briefly with Lt. Col. Willis O. Jackson and Lt. Col. Robert H. Cole, the 1st and 2d Battalion commanders, and Maj. Sherburne J. Heliker, the regimental S-3. General Clark told the infantry commanders: "You had better get on your hiking shoes. I'm going to throw you a long forward pass into the Po Valley, and I want you to go get it." Such was the long-range importance of the Giogo Pass attack.

About noon on 12 September, the regimental commander of the 338th Infantry, Col. William H. Mikkelsen, went to the 85th Division command post (CP) to receive the attack order. It called for the 338th Infantry on the left to take over part of the 363d Infantry zone for the main effort against Monte Altuzzo.

In mid afternoon of 12 September Colonel Mikkelsen, the 338th commander, issued the regimental attack order. The 1st Battalion, commanded by Colonel Jackson, was to make the main effort, seizing Hill 926, the crest of Monte Altuzzo. The 2d Battalion, under the command of Colonel Cole, was to attack on the left along Highway 6524 to Point 770, between Monticelli and Monte Altuzzo. The theory was that pressure along the highway would assist the main effort against Monte Altuzzo. In reserve the 3d Battalion, commanded by Maj. Lysle E. Kelley, was to follow the 1st up the main ridge. All battalions were to move soon after dark to forward assembly areas from which they were to launch the attack at 0600 the next morning. All three were at full strength, carried normal allowances of equipment and combat loads of ammunition, and could be reinforced from a regimental replacement pool of 250 men.

Difficulties in establishing the exact location of front-line units and faulty communications however soon disorganized the attack of the two point companies against the southern ridges of Monte Altuzzo (hill 782 and the Western ridge, soon renamed "Peabody Peak" from the name of Company B’s CO). The action soon disorganized into a series of firefights between small groups of soldiers on both sides. Several attempts at counterattacks by the defender were halted by US Artillery concentrations, often hitting staging areas before German troops could organize for attack, depleting the already hard-pressed 1st Battalion of the 12th Fallshirmjaeger Regiment. During the afternoon of 13 September the 338th Infantry learned through prisoners of war that a company of eighty men held a front of about two thousand yards from Monte Altuzzo to Monte Verruca. Although this force would not have been sufficient to man all the prepared positions in the area, it was large enough to occupy a number of strong points in the main line of resistance. In view of the small number of troops in position when the American attack was launched, the Germans were evidently waiting to see where the heaviest blow would fall. During the night of 13-14 September, replacements arrived for the companies on Monte Altuzzo and on the other mountains in the Giogo Pass sector. At least one group of two officers and thirty men arrived at the companies of the 12th Fallschirmjaeger Regiment.

Although some radio intercepts and prisoner of war reports had indicated an enemy withdrawal, the II Corps G-2 discounted such movement as being of a local nature only. Intelligence was received that all three battalions of the 12th Fallschirmjaeger Regiment were withdrawing, but the reported withdrawals were interpreted to be from outpost positions to the main line of resistance. On Monte Altuzzo the enemy's defenses were still intact except for the outpost positions which elements of the 363d and 338th Infantry had knocked out during the day. Even these positions were re-manned during the night. The Fourteenth Army was still not aware that the Fifth Army's main effort was being made up Highway 6524 toward the Giogo Pass. Expecting the principal attack at Futa Pass, the Germans planned to send one battalion of the Grenadier Lehr Brigade on the night of 14-15 September to the area south of Loiano as I Parachute Corps reserve.

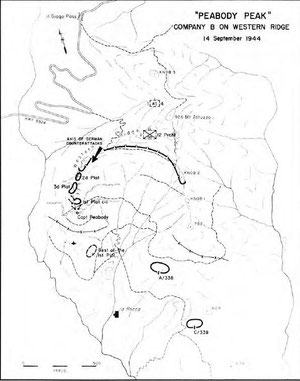

Peabody's Peak (Hill 782, September 14, 1944)

After failing for two days to breach the Giogo Pass defenses, II Corps prepared to continue the attack on 14 September, using the forward positions as the line of departure. The 338th Infantry was again to make the main effort against Monte Altuzzo. In the 338th Infantry's zone the 2nd Battalion was to drive along the highway to take Point 770, while the 1st Battalion was to strike again up the main ridge of Monte Altuzzo to capture the crest of the mountain. The 3d Battalion, in regimental reserve, was to move from its assembly area near Scarperia to the rear of the 1st Battalion. It was to follow the 1st up Monte Altuzzo on order, prepared to push north northeast to the hills about two miles beyond the Giogo Pass.

By the morning of 14 September the German forces on Monte Altuzzo were

numerically stronger than they had been the day before. During the night (13-14 September) the 1st Company, 4th Antitank Battalion (Kampfgruppe Hauser), with a total strength of between 90 and 150 men, was sent to reinforce elements of the 1st Battalion, 12th Fallschirmjaeger Regiment. Although these men sustained some casualties while moving into position, most of them arrived in Altuzzo's forward bunkers and were attached

either as individuals to the 1st Company or as a separate unit under the regiment. Initially forty-two men from the 4th Antitank Battalion were committed on the east flank of the 1st Company, 12th Fallschirmjaeger Regiment, but casualties reduced the number of effectives to twenty-five.

Though originally armed with 75-mm. assault (antitank) guns, the company had only its complement of ten machine guns for its Altuzzo defense.

Peabody Peak today in May 2022

Besides these reinforcements, the enemy had at least three understrength companies of the 12th Fallschirmjaeger Regiment in the vicinity of Monte Altuzzo: the 1st Company with forty-four men and the 3rd and 11th Companies with fifty to sixty men each. The German’s MLR on Altuzzo was manned by 250 to 300 men in all—numerically the equivalent of one understrength German battalion or one and one-half companies of American infantry.

During the day-long battle, Captain Peabody's men had penetrated the main line of resistance on the western ridge but had not occupied the main bunkers on the peak. Since they had not consolidated their gains, the attack was abortive. The company's flanks had been exposed continuously, because the units on its right and left were too far away to be of assistance or were out of contact. The only tangible gain from Company B's attack was the development for the first time of the strong enemy defense on Altuzzo's western peak. By the end of the day Company B could not have held its gains without reinforcement, for the day's casualties had sharply reduced its fighting power. Out of its strength at the jump-off of about 170 men, it had suffered ninety-six casualties including twenty-four killed, fifty-three wounded, and nineteen captured or missing in action. Even the survivors were in no condition to continue the battle or stand another harrowing day like 14 September. Under the circumstances Colonel Jackson had no choice but to withdraw Company B and renew the attack against Monte Altuzzo with fresh troops. To the men who had fought there so hard, the western ridge came to be known as Peabody's Peak.

In front of the Giogo Pass the troops of II Corps had failed everywhere on 14 September to breach the enemy's MLR and take the objectives which would outflank the Futa Pass. However, at the end of 14 September the Fourteenth Army was well aware that the 4th Fallschirmjaeger Division was bearing the brunt of the Fifth Army attack against the Gothic Line. But in light of Fourteenth Army reports the enemy had clearly not realized that US Fifth Army's main effort was restricted to the Giogo Pass area. The pressure along the whole II Corps front was such that the Germans still had not divined Fifth Army's plan of outflanking the Futa Pass by breaching the Gothic Line at the Giogo Pass.

On 15 September, the German command belatedly realized that the Giogo Pass attack constituted the main thrust by the US 5th Army. The 3rd battalion, 12th Fallshirmjaeger Regiment was hastily

brought forward, together with the scant reserves available to the whole Army Corps. These included 400 Lithuanian conscripts, most of whom surrendered to the GIs at the first opportunity.

By the end of 15 September the paratroopers of the 1st Battalion, 12th Regiment, in the Altuzzo

sector were in dire need of reinforcement. The 1st Company had suffered especially heavy losses, including the company commander's death on 14 September. By the time that the 1st Battalion,

338th, launched its attack late on 16 September, enemy reserves available for defense of the Giogo Pass had been seriously depleted. The 1st Battalion of the 12th Fallschirmjaeger Regiment

radioed its lower units on Monte Altuzzo that the American attack had to be held at all costs because no more reserves could be sent.

The 1st battalion, 338th Infantry finally reached the top of Mount Altuzzo on 16 September. The successful thrust on Mounts Pratone and Verruca on the right of the II Corps sector, September 17, substantially ended the fight. American troops finally secured the Giogo Pass on 18 September. Six days of battle had cost the US II Corps 2731 casualties. German casualties are unknown, but surely higher, most of them caused by Artillery fire hitting approaching troops behind the lines.

Besides killing and wounding a large number of Germans, the 338th Infantry captured many prisoners. Although an accurate breakdown of prisoner of war figures is not possible, probably close to 200 men were captured by the regiment. By 1200 on 18 September seventy-three prisoners had passed through the regimental cage since the start of the Gothic Line offensive, and during the twentyfour hours ending at 1200, 19 September, the total rose to 212. In view of the time required to process the prisoners and send them to the rear, the 338th Infantry's action was probably responsible for the capture of most if not all of them. The basic point was that the 338th Infantry and its supporting units had left the Germans with inadequate force to man their positions or to maintain a prolonged defense. The 12th Fallschirmjaeger Regiment, as well as the reserves of the 4th Fallschirmjager Division had suffered heavy losses.

Monte Altuzzo History Park May 2022

By the morning of 18 September, the troops of II Corps had seized an area seven miles in width on either side of the Giogo Pass. The Germans hard hit by heavy losses and the lack of reserves, were in full retreat toward the heights north of Firenzuola.

Because of the terrain, poor communications, and lack of control, at no single time during the battle did the Americans throw as many troops into action on Monte Altuzzo as did the German defenders.

Il Giogo Pass after the Battle

Gotica Toscana Museum

The CDHR offers documents, original WW2 footage and displays giving visitors the chance to get well informed with men, uniforms and equipment which were used and made history of the last and often overseen part of the Campaign in Italy.

Then an Now Il Giogo Pass

Relics

Acknowledgements:

-

Some text and some 1944 photos courtesy lonesentry.com

-

Wikipedia

-

Book “three battles” by Charles B. MacDonald & Sidney T. Mathews

-

Many thanks to our guide Alessio Cammeli and Andrea Gatti, Manuel Noferini as well as all the other we met who helped to made this an awesome tour