(Dedicated to my friend Virgil W.Westdale - veteran of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team)

The 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, units of the US Army made up of Americans of Japanese

ancestry. This is the story of their part in the Battle of Bruyères and Biffontaine as well as the their successful rescue of the "Lost Batallion" (1st Battalion of the 141st "Alamo" Regiment,

36th Texas-Division). The 442nd RCT lost more than 800 troops while rescuing 211 men behind enemy lines.

Those battles is also the climax of the Nisei’s battle against suspicion, intolerance, and a hatred that was conceived in some dark corner of the American mind and born in the flames that swept

Pearl Harbor.

Nestled in the beautiful valley. on the western edge of the Vosges. lies the small town of Bruyères. Roman relics found nearby date its origin to the 4th century A.D. Two centuries later, Ambron, son of Clodion-the-Long-Haired, built a castle of one of the four surrounding hills. In October 1944 a new chapter was to be added to the history of Bruyères, one written with the blood of Americans, Frenchmen and German locked in fierce and brutal combat on those four hills and the mountains stretching east toward St. Dié.

The town of Bruyères and points south of it were defended by the 716th Infantry division, commanded by 52 year old artillery officer Generalleutnant Wilhelm Richter.

On the American side, the attack was led by the 36th Texas Division. On September 29 1944, anticipating the American assault, the Germans blew up the railroad tunnel on the Bruyères-Epinal line

and set the station on fire. On the same day American artillery shells started to fall on the town and the surrounding hills-the first of thirty thousand.

On October 15 1944 the assault began. Spearheading the drive was the 442nd Rgt Combat Team, led by fifty year old Charles Wilbur Pence. At 0800 hours, Lt. Col. Gordon Singles's 100th Btl as well

as Lt. Col. James Hanley's 2nd Btl crossed the line of departure. The 3rd then closed in reserve behind the 100th. The 522nd Field Art Btl was in direct support, and the 232nd Combat Engineer

Comp played its usual role, lifting mines and reducing blocks so supplies could move. The attack launched on October 15 1944 progressed slowly all that day and the next, consisting of a yard by

yard advance in the face of a determined enemy.

In

front of them , like forbidding sentries rising a thousand feet from the valley floor, stood 4 strategic hills named A, B, C and D. The 100th Battalion's objective on the far left was Hill a

(Buemont), while Hill B (le Chàteau) half a mile south was the goal of the 2nd Battalion. The first enemy's encountered by the Nisei soldiers were Russians in German uniforms, who offered

little resistance. Far more difficult was the situation for the men of the 100th Battalion who faced the SS-Polizei Rgt 19.

The attack companies encountered minefields, roadblocks and machine-gun fires from the SS-Polizei Rgt 19, Grenadier Rgt 736 and 223 as well as from the Festungs-MG Btl 49. Unlike Italy where

the resistance had been fierce, in the Vosges Mountains the fighting would be brutal. Heavy mortar and artillery shells burst in the trees overhead, raining steel on the doughboys below who

could find few ways to protect themselves from the vicious tree bursts.

The aerial photo shows Bruyères and the surrounding Hills A, B, C and D.

Fighting for hill "A" and "B"

The 100th Btl attacked hill "A", the 2nd Btl attacked hill "B", but after a day of severe fighting, the Nisei gained barely five hundred yards by the end of October 15.

On the morning of the October 16 , the 100th Btl, attacking on the left, had presumably cleared a roadblock. After the battalion had passed on, a few enemy diehards cut loose a blast of small arms fire on the engineer party that came forward to remove it causing five casualties. The engineers withdrew to cover, reorganized, and promptly launched an attack on the defenders, driving them out. They then proceeded with the day's work of blasting out the tangle of logs, wire, and mines that made the road impassable. This was indeed, a new and more devastating war than any of the US troops had previously experienced.

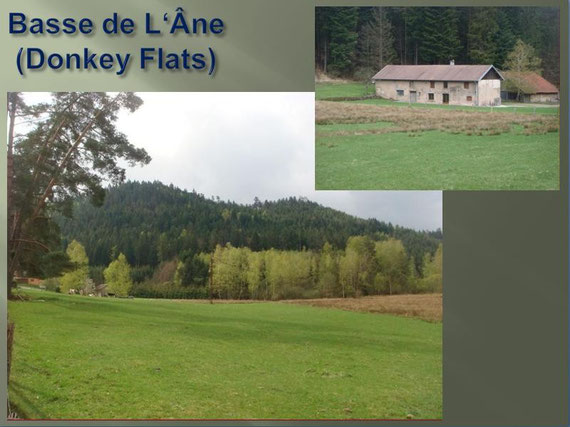

Basse de l'Âne (Donkey Flats)

As Companies E and F fought teir way toward Hill B, Capt. Pershing Nakada's engineers treid desperately to clear the roadblocks and mines ahead. But when the two attack companies reached open ground, they were again pinned down by murderous fire from Hill 555 and Hill B. The sam was a fact for the 100th Battaltion on the left. After Companies A and C cleard their sector around Hill 555, they were stopped short at the open valley known as Basse de l'Âne (Donkey Flats). The photo shows Hill 555.

It was to be an all-day effort, through cold rain and relentless German pounding, before Company F finally took Hill 555 withs its commanding view of Bruyères and the surrounding hills. But as an evening mist began to cloak Donkey Flats, the Germans launched a counterattack. It was still raining at dawn, 17 October, as General Dalquist urged his 143rd Regiment, to take Champ le Duc, defended by the Grenadier Regiment 736.

Once again, the Americans were welcomed by an artillery barrage - fifty well placed shells and concentrated machinegun and sniper fire from the stone houses (see photo). A second German counterattack hit the 100th Battaltion just as its forward platoons were jumping off. The Nisei eventuelly turned the tide, but as soon as the lead elements reached Donkey Flats, they fell victim to a German hell fire from Hills A and B and once again the stone houses.

Hill B

By noon of the 17th , the 100th Btl had advanced as far as the first of four conical hills that towered over Bruyères. The 2nd Btl on the right kept pace, driving back two determined counterattacks and launching an attack on Hill "B," second of the four hills. Meanwhile, the 3rd Btl swung quietly into position on the right of the 2nd Btl on the night of the 17th. The photo shows Hill B from Hill D.

The

following morning, all three battalions mounted a battering-ram attack behind a screen of fire from the 522nd Field Artillery Btl and other elements of division artillery.

Hill "A" fell to the 100th Btl at 1400 hours on October 18 1944, yielding more than 30 prisoners, and by the end of the day, Hill "B" had fallen to the combined efforts of the 2nd and 3rd

Btl.

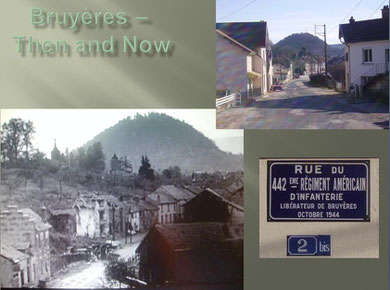

Bruyères

L Company of the 3rd Btl had also pushed into the north end of Bruyères and was proceeding to a linkup with the 143rd Infantry, which had attacked the town from the south, but the Germans still held hills "C" and "D". Bruyères had fallen! Only on Stanislas Square did a group of die hard defenders hold out until midnight. The last big explosions came when Capt. Pershing Nakada’s 232rd Engineer Company blew up the concrete barricades around the town hall. The photo shows the road were the Americans first entered Bruyères.

With

Bruyères in American hands, the next objective was Hill "D" east of town. The attack was launched at 1000 hours on October 19.

Hill "D" fell to the 3rd Btl around noon on the 19th October, and Hill "C," now somewhat in the rear of both the 2nd and 3rd Btl had now developed into a bedlam, with large pockets of

enemy troops (left on Hill "D" and by-passed in the attack) opening fire on the reserve companies and command posts.

During the fight to take Hill "D", F Company was trying to dislodge a German company that had infiltrated Hill "D" during the night. The battle was at deadlock when the Germans wounded

Tsg. Abraham Ohama from F Company, disregarding his white flag while on the way to aid a fellow soldier. As the litter bearers tried to get to both of them, the Germans ignored the men

with the Red Cross helmets and opened up on them, wounding the medics and killing Ohama. Infuriated that the enemy shot an unarmed, wounded man, the F Company men charged up the hill and

annihilated the Germans. Those soldiers attacked with such ferocity that soon more than fifty German Grenadiers lay dead and seven survived only by hiding until the following morning.

This was later called the "Banzai charge".

The Battle for Bruyères is considered one of the ten worst disasters in the history of the US Armed Forces!

Biffontaine

Dahlquist ordered

the 100th Btl to march east, more than a mile from the nearest friendly troops, and take the high ground overlooking the village of Biffontaine. The men reached the ridge and dug in, but soon

they were being hit from all three sides with German artillery, rockets and anti-aircraft fire.

Although they held the ridge, the men were critically low on water and supplies. Five tanks loaded with ammunition and water and accompanied by a platoon tried to reach the 100th Btl. But the

Germans ambushed them, killing three and wounding several others. Meanwhile, German bicycle troops attacked the 100th along the right rear flank. The 2nd Btl beat off the attack, but the 100th

Btl still needed supplies. Finally soldiers from G and L Companies, carrying water and ammunition on their backs, found their way through the thick forest with the help of the French resistance

and relieved the beleaguered 100th Battalion.

Dahlquist then ordered the 100th to descend the ridge and take Biffontaine, an objective that many men thought was tactically worthless. On the morning of October 23, the 100th Btl climbed down and quickly captured 23 Germans, some enemy arms and several houses. But soon the Germans re-grouped. They surrounded the town and blasted the 100th with anti-aircraft cannons and tank fire all through the night. Exhausted, the men in the 100th huddled in the cellars of ruined buildings.

Many had not slept for eight days. The casualties were piling up. Their cache of captured weapons had run out and the supply lines were again cut off. The Germans swarmed among the houses yelling, "Surrender," but the 100th Battalion held the town.

The next morning a Nisei litter train made up of medics from the 100th and the 3rd Btl, along with German prisoners acting as litter bearers, attempted to carry out some of the wounded. The group had barely left Biffontaine, when a German patrol captured them. Only three of the 20 were able to escape. Even today, evidence of the Battle can be found today. On the afternoon of October 24, the 3rd Battalion finally broke through to free the 100th. Biffontaine, a farming hamlet of 300 people, with no rail line, was now in Allied hands. The cost for the 100th Battalion: 21 K.I.A., 122 wounded and 18 captured.

(Text courtesy Michael Higgins - son of 1st Lt Martin J. Higgins)

The Vosges town of Bruyères, liberated on 18 October 1944, was less than 45 miles west of the Rhine. Desperate German troops were determined to make the Americans pay dearly for this territory. In recorded military history, no army had been able to do what the U.S. Seventh Army was about to attempt to do: Defeat an enemy force defending the Vosges Mountains. Enter "Operation Dogface." Situated directly in the path of the Americans lie the Foret Dominale de Champ and in October this wood was a cold, dark, nearly impenetrable place covered with fir trees from 60 to 200 feet tall. In some places, little sunlight reached the forest floor - here the forest resembled a dark green cavern. A near constant rain added to the gloom. Numerous fir trees greatly reduced fields of fire - but offered exceptional cover for German snipers. The weather during the last week of October 1944 included a persistent near-freezing rain and scattered dustings of light snow.

"Operation Dogface" in the Low Vosges was a coordinated U.S. Seventh Army spearhead engaging all three divisions of VI Corps: the 45th, the 3rd and the 36th. The tip of the 36th's spear was Company A, 1st Battalion, 141st Regiment.

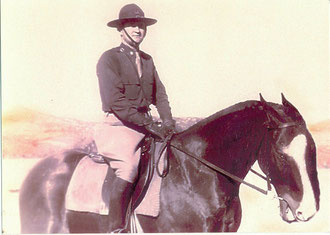

Leading Co. A, was 28 year-old former Horse cavalryman 1st Lt. Martin J. Higgins, Jr. from Jersey City, New Jersey. Martin "Marty" Higgins joined Troop B (machine gun troop) of Squadron C, 101st Horse Cavalry Regiment, New York National Guard (at the Bedford Avenue Armory in Brooklyn) as a Private immediately after graduating from College, in 1939. After rising to the rank of sergeant, he attended Officer Candidate School at Fort Riley, Kansas; graduating as a 2nd Lt. in 1942. Higgins served with the famed “Buffalo Soldiers” of the 10th (Horse) Cavalry Regiment, 2nd Cavalry Division, until the unit was disbanded in North Africa during March 1944.

Higgins and three other officers, Lt. Colonel James H. Critchfield, Lt. Colonel Donald J. MacGrath and Lieutenant Harry G. Huberth; formed a cadre of officers, who joined the 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th "Texas" Infantry Division in Italy. Lt. Higgins would incorporate cavalry combat tactics into the execution of his missions whenever possible. At a briefing for "Operation Dogface," Higgins learned his orders were to lead the 1st Battalion, 141st Regiment, on foot, up the trail into the Foret Dominale de Champ, move east, and take the heights above La Houssiere. Higgins advised 1st Battalion Commander, Colonel William Bird, whom he greatly admired: "If a strong force did not stay close to the 1st Battalion, a gap could form which the Germans might easily exploit and surround his unit." Colonel Bird took that observation under advisement and told Higgins: “A strong force will follow, move out.”

The goal of "Operation Dogface" was to eject the 19th German Army from the Vosges Mountains and move on to the Alsatian plain where terrain would allow the American advantages of armor, artillery, and air-support to be bought to bear. If "Dogface" succeeded, it would position the Germans with their backs to the Meurthe River. However, in the Vosges, the advantage fell to the well-entrenched German defenders. The rugged terrain of the western Vosges limited the movement of American armor and artillery, while the weather would negate American air support. After the company commanders of 1st Battalion briefed the non-commissioned officers they jumped-off from their line of departure and proceeded along the "axis of attack."

The Lost Battalion

For the sake of clarity, the "Lost Battalion" was at the time, not a full battalion. To fully appreciate the situation of the 1st Battalion, one needs to consider the following numbers. During WWII, in the U.S. Army:

1.) a Squad usually numbered 12 men or less

2.) a Section usually numbered 20 to 23 men

3.) a Platoon numbered between 40 to 55 men

4.) a Company numbered between 80 to 200 men

5.) a Battalion numbered anywhere between 300 to 850 men

At approximately 270 men, 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry Regiment, now cut-off, would certainly be considered numerically "under strength." The Battalion was not lost in the geographic sense. They knew exactly where they were, the 141st Infantry command knew exactly where the cut-off men were, and the German 338th Infantry-Division knew generally where the men of the 1/141st was situated. What the Germans did not know was the tenuous condition of 1/141st. By 23 October 1944, the 1st Battalion, 141st had been “in the line,” engaged, for the 70 consecutive days since the invasion landing in Southern France on August 15, 1944.

October 23, 1944

The mission commenced under leaden skies and intermittent rain at 1158 hrs on 23 October. Unknown to the Seventh Army, the German 19th Army was to receive 3000 reinforcements during the next two days. Company A 1/141 was heading into a trap. Two miles up the trail Able Company encountered a Jerry (Germans) force on its right flank armed with automatic weapons. Able Company destroyed the German force and continued toward its objective. By 1745 hrs on the 23rd, Company A was on hill 624. They consolidated their position with the remainder of 1st Battalion, 141st.

October 24, 1944

On the morning of 24 October, one platoon of Able Company stayed behind to assist with the battalion command post to be established where Able Company had just spent the previous night. Meanwhile, 1st Battalion 141st proceeded toward the heights above La Houssiere in the following order: Baker, Charlie, Able. Two hours later, Able Company sent a patrol from its 2nd platoon to ensure its supply route. About this time Baker was attacked by two groups of Germans that Lt. Huberth and his men repulsed after an intense firefight. Able Company encountered the enemy in the Bois de Biffontaine, near hill 665. Lt Higgins and his men repelled the German force. The enemy attacked the 141st along its flanks all day.

Later that afternoon, Co. A (minus its mortar platoon) engaged in a fire-fight with a large enemy force, estimated at "Company strength" that had worked its way up the trail from Devant le Feys (further to the south). Meanwhile, near hill 645, Co. B and Co. C, were also hotly engaged. All elements of 1 / 141st had been attacked on their flanks by a numerically superior enemy force, comprised of the 933rd Volks-Grenadier Infantry and the 198th Fusilier Battalion.

With this action, the enemy separated an estimated 270 men of the lead Companies (A, B, C, & the weapons platoon of D) plus their two Forces Françaises de l'Intérieur (FFI) guides (Henri Grandjean and Pierre Poirat), from the rest of the battalion. The Germans overran 1st Battalion HQ. This assault overwhelmed the Americans, forcing Colonel Bird and his men to fall back. The Germans quickly set up a formidable roadblock made by felling approximately 80 huge fir trees that fell in interlocking order. They covered the road with "box" mines or "Schuh" mines, and constructed a gauntlet of machine guns and anti-tank weapons such as Panzerschreck and Panzerfaust on both sides of the road - ahead of, and behind, the roadblock. This further isolated the lead elements. The reduction of this road-block would keep the 36th Division's 111th Combat Engineer Battalion and elements of Company C 232nd Engineers busy for several days.

The 1st Battalion command elements were now separated from the lead companies. This left the three company commanders: Co. A, 1st Lt. Martin J. Higgins; Co. B, 1st Lt. Harry G. Huberth; Co. C, 1st Lt. Joseph P. Kimble, and Co. D; 2nd Platoon Commander 1st Lt. Gordon E. Nelson, as the senior-ranking officers. Also with the battalion was 2nd Lt. Erwin H. Blonder, a Field Artillery Observer, whose radio would provide the only communications with the outside. The batteries on Blonder’s 300Mc (megacycle) radio had a life expectancy of two days. Blonder nursed them to last six.

On the evening of 24 October, 1st Battalion learned it was cut-off when litter bearers who had been sent down the trail to the Battalion aid station returned with the wounded and news they had been attacked. Three men from the patrol sent to secure the supply route also returned and reported that Able, Baker, Charlie and part of Dog Company were now cut-off. A small patrol was immediately sent to confirm this news. Two men stepped on mines. The remainder of the patrol returned.

The three company CO’s, Lt. Nelson, and Lt. Blonder decided they would work in concert, and that 1st Lt. Higgins would assume overall command. Lt. Higgins and Lt. Huberth had served together in the 10th (Horse) Cavalry Regiment. Coming up the Rhone Valley, Co A and Co B had fought a number of engagements together. A strong bond formed between Higgins and Huberth during those actions, especially during the Moselle River crossing and subsequent engagements in the villages of Remiremont, St. Entienne, and St. Ame.

Nelson and Higgins had also worked together during the Rhone Valley advance and had experienced some narrow escapes - like the time they were conversing and a German mortar round landed directly between them - but did not detonate. The four officers gathered to confer. Upon seeing Lt. Gordon Nelson, who he always jokingly called "Gene," Lt. Higgins smiled, shook his head, and said: "Well, what now, Gene?"

A successful conclusion to the situation at hand would require teamwork. Lt. Higgins worked closely with 1st Lieutenants Huberth, Nelson, and Kimble. Acting commander 1st Lt. Higgins gave the order to "dig-in," and established a defensive perimeter in a region of the Foret de Champ known as Le trapin des saules. Ironically, Le trapin des saules is Vosgesoise slang meaning “the trap of the Willows”.

As the 141st had been on the offensive since the landing, Higgins had never given this order before while in France. This was the first time they assumed a defensive posture and had to dig-in. The perimeter more or less straddled the trail in a 350-yard elliptical-shaped circle anchored with a 1917-type .30 caliber water-cooled “heavy” machine gun at opposing ends. Manning the two guns would be the ten men of Lt. Gordon Nelson's Weapons platoon of Company D. One gun was under the able direction of S/Sgt. Bruce Estes and the other was under 20 year-old, Sgt. Jack Wilson, a seasoned veteran of the Italian Campaign. The Battalion also had 81mm mortars, but with the dense tree cover (unlike the Germans) had no clear field of fire to bring them to bear. The defensive perimeter bristled with BARs, M-1 rifles, .30 caliber carbines, bazookas, plus the six .30 caliber “light” machine guns of each rifle Company. By forcing the 1st Battalion to dig-in, the dynamics of this engagement changed. Now, the Germans, despite their numerical advantage, would face a well-entrenched American force. The Germans would also forfeit the advantage of their entrenched positions in an effort to reduce the American force.

An entrenched position is, generally, considered capable of repelling a force three times its number. The American defensive perimeter presented a formidable array of firepower, as the Germans would soon learn. “The perimeter had listening outposts some 75 to 150 yards in front of each platoon, offering 360 degree protection,” Lt. Higgins recalled. Each listening post was connected to the Command Post (CP), inside the perimeter, by sound-power (wire) phones. There would be no surprise German attacks. Each listening post tracked German movements and reported them to the CP, who then contacted Regimental HQ to request artillery fire missions. The evening of 24 –25 October was punctuated by intermittent enemy artillery fire. Three men, including 1st Lt. Charles R. Mattis of Company A, were killed in the German artillery barrage before it was suppressed by counter-battery fire from 131st Field Artillery, 36th Division. As the situation unfolded, at regimental HQ, the Americans learned from a captured German Battalion commander who had been sent to the rear, that the position in which 1st Battalion found itself was part of an orchestrated trap. He informed his interrogators that the Germans were aware of the American avenues of approach and had possession of the battle plan and maps for "Operation Dogface." The German officer went on to report that he had orders from “the top” to annihilate this trapped battalion. The 933rd Volks-Grenadiers' orders were simple: "Stop the Americans at all costs."

October 25, 1944

On the morning of 25 October the "Lost Battalion" sent out a patrol to try and break through the German force separating them from the rest of the 141st Regiment. This patrol soon returned. It was decided a larger, 48-man patrol might succeed. This patrol, under the command of 2nd Lt. James Gilman, of Charlie Company, and led by Able Company's S/Sgt. Harold C. Kripisch headed back down the trail to wipe out the enemy in the rear. They were also tasked with making contact with the mission patrol (2nd Battalion, 141st Regiment) trying to make their way to the Lost Battalion with rations. Meanwhile, 2nd Battalion, 141st Regiment radioed 1st Battalion they were stalled and had encountered heavy resistance from small groups of aggressive German troops. Lt. Gilman's patrol traversed a distance of 1000 yards before it encountered a medium-density minefield arrayed with the dreaded “S” mine, nicknamed the "Bouncing Betty." The "S" mine was a particularly devilish spring-loaded device usually filled with about 360 ball bearings or pieces of scrap steel. S/Sgt. Kripisch who carried a .30 caliber Browning Automatic Rifle, noticed the mines he and his men uncovered on an earlier patrol had been covered with dirt. He spread the word to his patrol to be on lookout for booby traps.

One "T-patcher” was seriously wounded when a booby-trap set-off one of the mines. The explosion alerted the Germans. A desperate nighttime fire-fight ensued. The minefield plus intense German mortar and machine gun fire stopped the patrol in its tracks. Pfc. Cunningham, who wielded another of the unit's .30 caliber Browning Automatic Rifles tried working his way around to the left to catch the Germans in enfilading fire. In the melee, he and another member of the patrol captured a German soldier. Cunningham remembered how the five men and their prisoner survived the ambush:

In the darkness and confusion we scrambled and took shelter under a ledge. We stayed there - me with my back pressing the prisoner into the back of the ledge - until we were sure the Germans had gone...and then we made our way back up the trail.

October 26, 1944

Only five men of the 48-man patrol returned - with one prisoner on the morning of 26 October. The rest of the patrol was MIA: presumed killed, or captured. Of those who returned, 1st Lt. Harry Huberth said: "They were lucky to get back to our foxholes." Despite these events, Higgins radioed: “Morale high.” Throughout the day, the Germans sent small patrols to attack the Lost Battalion. Each assault was repelled. On the evening of 26 October the Lost Battalion was ordered to move out and make contact with the advancing elements of the 100/442nd RCT as Colonel Charles W. Pence was directed to relieve the 3rd Battalion, 141st Infantry, with one Battalion, 442nd Infantry, and elected to send the 2nd Battalion into the line. They jumped-off in the following order: Charlie, Baker, Able - with Able Company protecting the wounded. In the van, Charlie Company encountered a strong enemy force blocking their advance. Charlie tried to out-flank the Jerries but were stopped by a large mine field. The Lost Battalion was forced to fall back to its original position of the evening of 24 October - overlooking their objective.

Co. A (less 1st and 2nd platoons), Co. B, Co. C, and Co. D had been surrounded and subjected to enemy artillery and mortar attacks for four consecutive days. In this sector, the artillery of German “Group Eschrich” situated between La Houssiere and Vanémont, included a K-18 self-propelled 170mm heavy gun, Nebelwerfer and 88’s. In the Vosges, artillery barrages usually meant "tree-bursts" from German "88s." The tree-burst artillery shell was pre-set to explode on contact with the upper tree branches of the tall fir trees - sending spear-like splintered tree branches and flaming iron shrapnel down upon the GI's below in a horrific seventy-foot free-falling squall of pain. It was said tree-burst showers sounded like a rapidly approaching swarm of angry bees. A fair amount of casualties in the Lost Battalion were attributed to tree-bursts. Men quickly learned to dig deep and cover their foxholes with tree branches and dirt. Inside the defensive perimeter, the "Lost Battalion" reported 28 casualties and three KIA. Higgins and his men had no food or medical supplies. They had run out of rations three days earlier. Ammunition was critically low. They had no clean drinking water (save a contested muddy spring used by German and American troops alike). Unlike the German commander who placed snipers near the water hole, Lt. Higgins gave specific orders not to shoot Germans at the water hole. He did not want the water hole contaminated. On one day a Soldier of the Lost Battalion shot a German who was just about to take water. After he shot him, the American searched the dead German and found poison - so it is most likely to assume that the German did not want to resupply his water but to poison the water hole. The combat range between both sides have been just about 25 meters.

The Lost Battalion had encountered enemy forces at three different points.

To remedy this situation, 1st Lieutenant Higgins, requested an air-drop. Forward artillery observer, Erwin Blonder, sent the message on the 26th, he gave the drop-zone coordinates as 349573, on Hill 651. On 26 October the 443rd Anti-Aircraft Battalion alerted its batteries A, B, C, and D: "at 0800, on October 27, friendly planes will drop supplies to the beleaguered men." The 443rd Anti-Aircraft Battalion had recently, been attached to the 36th Infantry Division. The 141th Regiment first requested XII-TAC send water, K-rations, ammunition consisting of:

- .45 caliber - one case

- Carbine ammunition - one case

- Machine gun ammunition - two cases

- .30 caliber M-1 ammunition - four cases

Radio batteries:

- BA70 - four

- BA 39 - six

- BA40 -six

However, by 1800, 141th Regiment radioed the Lost Battalion that food, water, and ammunition would be dropped at coordinates 344574 instead of the original coordinates. At 2015 Lt. Higgins sent the following message to Regimental HQ: "Small clearing around our position. Will mark with white arrow and, if possible yellow smoke at 0745. Request rations, ammo, cigarettes, medical supplies, batteries. Have aircraft drop supplies so enemy will not observe and inform enemy our position."

The 1/141 got to work preparing the drop-zone. Parka liners, maps, and t-shirts torn into strips made a 25-foot arrow on the forward slope, pointing west. Smoke grenades were tied to small trees and were bent-over to make their detonation automatic. As the planes approached, the grenades would be released - sending smoke wafting above the treetops. At 2145, Regimental HQ informed Lt. Higgins to "launch smoke when aircraft approach," and then radioed back to Lt. Higgins at 2350: "Aircraft will drop supply at 1100 with strong force coming."

Ground Crew Armorer Sgt. Louis Cellitti with the 405th Squadron who rigged aircraft with ammunition for that mission relates:

"Trucks were brought in and the supplies were stuffed into the belly tanks and affixed to the planes to be dropped." It was a point of pride for Sgt. Cellitti that all of “his” pilots came home from their missions safely.

During World War II the P-47 had five different types of auxiliary tanks, of which three were in use during October 1944:

A 75 US gallon drop tank, a 108- gallon drop tank and a 150 gallon drop tank.

As bad as the weather had been during the last week of October 1944 for the men of the 36th Division on the ground - it had been abysmal in the air. Intense fog, near-constant thick cloud cover, and a persistent near freezing rain kept the 371st Fighter Group grounded since 23 October.

October 27, 1944

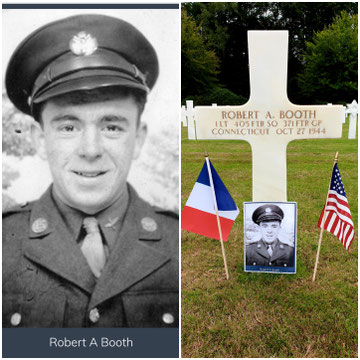

On 27 October, the weather was so bad that 405th Squadron would be the only unit airborne, in the entire Ninth Air Force and the XII TAC, in all of France. The mission was ordered only because of the desperate situation of 1st Battalion in the Foret de Champ. At 1045, two flights of eight P-47D aircraft of the 405th Fighter Squadron (371st Fighter Group, 70th Wing, 9th U.S. Air Force; based at Dole/Travaux), one designated "Green Flight," took off for the "Lost Battalion" drop zone approximately 100 miles to the northeast. The planes were carrying two-150 gallon wing tanks, each filled with food, medical supplies, ammo and radio batteries for the beleaguered troops of the 1st Bn / 141st. The flight attempted to fly under the overcast and maintain contact with ground checkpoints. The squadron referred to a mission as “the show.” On this particular “show,” to facilitate the mission, the flight flew "in-string," one behind the other, 2nd Lt. Robert A. Booth, of Oakville, Connecticut, flew "Green Four," in fourth position. As the flight approached Fougerolles, it encountered intense overcast skies.

Green Flight leader, 1st Lt. Paul R. Tetrick, stated:

We were trying to get up through the valley where the dead-end railroad leading northeast from Fougeroles is located. Captain (Gavin C. Robertson), who was leading the section, seeing it was useless to continue further, called twice for us to give it the throttle and pull up through the overcast. Being that we were somewhat "in string" it was impossible to reform and go through (the clouds) in formation, so we went up individually. The last I saw of Green Four (Lt. Booth) was just as we entered the clouds following closely behind Green Three.

Green Flight climbed above the weather and regrouped. This meant switching from contact (or visual) to instrument flying. Lt. Booth failed to regroup with his flight above the overcast. Attempts to reach Lt. Booth by radio were unsuccessful. As his flight would later learn, 2nd Lt. Robert A. Booth, had "spun-in" and slammed into a mountainside at position K-157396, five miles east of the village of Fougerolles. His aircraft burst into flames upon impact. According to the accident report, it is suspected that 2nd Lt. Booth lost control of his aircraft after transitioning from contact to instrument flying - just prior to entering heavy cloud cover. Lt. Booth was promoted to 1st Lieutenant. He earned the Distinguished Flying Cross, 9 Oak Leaf clusters on his Air Medal and the Purple Heart. 1st Lt. Robert A. Booth is buried in Plot B, Row 12, Grave 23, at Epinal American Cemetery, Epinal, France. He was the first casualty of the 405th Fighter Squadron.

Green Flight arrived over the drop zone at 1115, but found the "target" was 10/10, completely obscured by cloud cover with a Stratus base at 200 feet, and returned to base without dropping any supplies. On the return flight, in the restricted visibility, Major Leonard's wing tip struck a treetop. Although this considerably damaged his aircraft, Major John W. Leonard was able to bring his ship home. Green Flight arrived back at Dole at 1235 hrs with parachutes and supplies still hanging from the wings. At noon the weather broke.

Artillery Forward observer Erwin Blonder, with the "Lost Battalion", called HQ to advise of the change in weather: Weather is clear now. Please do something.

Pilot Robert “Bob” L. Griffith, of Woodland, California, recalled the air-drop mission was one of his early missions. It stood out in his mind because he remembered he was concerned, not so much about any Germans he might encounter, but they were going to be flying at a high rate of speed - and the visibility was nil! He recalled they took off in-formation, that is side-by-side, two at a time. He said this was something the squadron rarely did. Many pilots had not done that since flight school.

Veteran 405th pilot, Milton Seal, of Victoria, Texas, recounted the squadron's efforts:

We were told there was an infantry battalion trapped on a hill somewhere near St. Die. They were running out of food, ammunition, medical supplies and were in a hell of a shape surrounded by Germans. Our squadron was chosen to try to get supplies to them. Supplies stuffed into some sort of duffle bag were strapped onto our bomb racks. So as we made our pass on the hill we could release them to drop to our troops. The weather was not cooperating so it was a difficult task. The first attempt...cost us one pilot and his plane.

Early on the morning of 27 October, the Lost Battalion repulsed an assault on their position, from the south, made by an enemy patrol supported by machine guns. The German MG42 machine gun made a distinctly unique sound. Due to the MG42's extremely high rate of fire, between 1400 and 1800 rounds per minute, some soldiers said it sounded like someone tearing a piece of material. Pfc. Arthur W. Cunningham, of Halston, Virginia, remembered seeing one German machine gunner that had been killed early in the assault - his body lay slumped over his weapon for the next four days.

The last transmission of the day was at 1945hrs, Lt. Higgins asked Lt. Blonder to send the following request to Regimental HQ: "Need halazone. Men weak, nine litter. 1st and 2nd platoons "A" not known. 4 killed."

The 442nd RCT point of view to rescue the Lost Battalion

During October 27, however, the entire 442nd Combat Team was ordered into the line in an effort to relieve pressure on the 1st Btl, 141st Infantry. In a push down the long heavily-wooded ridge that extended southeast and dominated the valley from Biffontaine to La Houssiere, the 1st Btl, 141st Infantry, which took and held hill 679 overlooking La Houssiere on October 24, had overextended itself and had been cut off by strong enemy forces.

Moving quickly, the 3rd Btl and 100th Btl pushed off from Belmont in pitch darkness at 0400, 27 October. By 1000 hours they had passed through the remainder of the 141st, which had been trying to break through to its besieged troops. The 442nd RCT launched its attack, battalions abreast, with the 100th on the right.

Progress was slow on the October 27. The terrain was next to impossible, heavily forested and carpeted with a dense growth of underbrush. Fighting went back to the days of America's Indian wars; every tree and every bush were carefully investigated before the troops passed on. Then, abruptly, the enemy drove the friendly troops off the high ground to the left flank of the 3rd Btl, opening that battalion to two major counterattacks, supported by a Mark IV tank and an armored car.

October 28, 1944

On 28 October, the 405th flew four air drop missions. The first flight of four P-47D aircraft took off at 0750 and was over the "Lost Battalion" drop zone at 0830. German flak was "Intense, accurate, and heavy." They made their drop and returned to Dole at 1047. The supplies floated to the forest floor beneath yellow, orange, and red parachutes. Some parachutes were snagged in the treetops. Two men from Charlie Company, Pvt. Peter Bondar and Sgt. James Comstock climbed a fir tree in excess of 100 feet to cut down the brightly colored parachute material, lest it give away their position to German artillery observers. Some of the supplies landed in German held territory and it was necessary to fight to retrieve them. A fair number of the American soldiers made scarves or neckerchiefs out of the parachute material.

The second “show” was also led by 405th Squadron commander Major John W. Leonard. He decided to try two ships at a time. Major Leonard from St. Petersburg, Florida, was a graduate of West Point, Class of 1942. He was greatly liked by his men. At 1052, Regimental HQ radioed Lt. Higgins: "Two aircraft at one time will drop. Total 10 aircraft." The flight took- off at 1115 and was over the drop zone target only to find it 10/10, completely obscured, turned about and headed for home. As they headed for base Y-7

at Dole, their course took them over Epinal and an encounter with an American M-16 armored half-track “Flak-Wagon”. The M-16 quad-mounted .50 caliber machine guns were capable of firing approximately 2200 rounds per minute. The standard .50 cal belt-load sequence was 1 tracer, 2 incendiary, 1 armor piercing (AP).

Milton Seale who flew wingman for Major Leonard on that mission recalls:

Major John Leonard and I were the first twosome. We were going along fine just under the clouds that gave us 200-300 feet above the ground. All of a sudden, we passed over a small valley, a stream of tracers were directed straight into John's plane. I was too low to get my nose down to fire back at the source, but I did see that it was our own people with a half-track vehicle mounted with quad .50 caliber machine guns. As I looked over at my partner, I said "John, you'd better get out of that thing...It's on fire." John, in his southern accent, said, "Yeah, it's getting a little warm in here. I think I'll bail out." Major Leonard turned his P-47 over and while fling upside down opened the canopy and bailed out. His chute unfurled and as his body disappeared in the trees, I saw the chute pop open then quickly float down to the trees. He could not have been more than 250 feet above the ground when he bailed out so I thought he had bought it. A general's field HQ near Epinal was situated a few hundred yards from where Major Leonard was hanging in a tree with his feet about six inches above the ground. A jeep was dispatched to pick him up.

Robert Lindsay, a Ground Crew Armorer for the 405th recalled what happened next:

The general dispatched a jeep to pick-up Major Leonard from where he landed in the trees. The major found the soldier who commanded the quad-50 gun crew and had a heated "discussion" with him - most likely about Allied aircraft identification.

In the restricted visibility, two P-47D aircraft approaching at a high rate of speed, from the west (German-held territory), and at a low altitude, with similar profile and bubble-top canopies might have been mistaken for two Focke-Wulf 190-D-9 aircraft.

Major Leonard returned to Y-7, Dole, in time to lead Sunday's (October 29) successful missions. In Major Leonard's absence, Lt. Edward J. Hayes led the third “show” of 28 October, with four P-47D aircraft. The flight took off at 1200 hrs. They were over the drop zone by 1245. German flak was "intense, accurate, and heavy." Supplies were dropped south of the drop zone. The flight returned to base at 1430.

At 1405 a radio message from Regimental HQ to Lt. Higgins asked: "Did you get supply? Do you need ammunition?" Lt. Higgins answered in the clear, "No, to first, Yes, to second." The fourth and final mission of the day used ten P-47D aircraft. The flights took off at 1545 and were over the target by 1630. All supplies were dropped in a wooded area, V-340570; near the top of the hill. The flights returned to base at 1735 hours.

A new plan called for 105 mm and 155mm artillery shells to be filled with chocolate "D" bars, wound tablets, and halazone tablets. Higgins put it this way:

We just crouched in our foxholes and sweated out the "attack" like we would have if the Germans had been shelling us. Those shells may have had chocolate in them but if they hit you, they’d kill you. We decided to take a chance. We figured, if you don’t get hit - you eat. One hundred such shells were prepared for firing. At 1640, guns of the 131st Field Artillery commenced a close-in fire mission. Shells were falling in the American sector. With the radio batteries dropped by the 405th Squadron, 1st Lt. Higgins sent the following message by walkie-talkie on 28 October 1944:

Thank our pals in the Air Corps: We eat for the first time in three days!

With the onset of the New Moon, the night of 28 October was the darkest. However, the next day would be the darkest in another sense. The Germans soon grasped the magnitude of the desperate situation facing the 1/141st and they prepared to close for the kill.

The 442nd RCT point of view to rescue the Lost Battalion

Saturday, October 28th, both Battalions continued the drive forward in the teeth of stubborn resistance and heavy artillery and mortar fire. Casualties went up and up, caused largely by tree bursts, from which there was no escape. Our own artillery was active, and the Cannon Company and 4.2 mortars performed yeoman service, but the Germans were below ground, while our troops were up and moving forwards. Foxeholes still visible all over the place. At the end of the day, the regiment was 1,500 yards nearer to the "Lost Battalion," but only at a terrible cost in men and material. During the night, biting cold and rain kept the men from resting. Foxholes can still be seen today.

October 29, 1944

October 29th, the sixth day, was the toughest. A tremendous artillery barrage preceded the first assault of the day. The deafening thunder of the barrage gave way to the staccato sound of German gunfire, including the unique sound of the German MG42 machine gun, signaled the commencement of the attack. Lt. Higgins signed off on a letter he was writing to his wife: "Time-out for a while, Marge, I've got work to do." He folded the letter in a square piece of orange parachute and put in his wallet.

Years later, reflecting on the action of that day, “The sixth day,” Lt. Higgins recalled, “The Jerries attacked us all day with small arms, machine guns, and mortars.”

Lt. Joseph Kimble, of Company C, concurred: The Germans were boring in from all sides and we were holding them off with grenades and bazookas.

Lt. Gordon Nelson of Company D, recalled: The Jerries kept coming at us. They must have had some new Lieutenant. He hit us five times and he must have walked away with about two men. Prior to the sixth day, the riflemen held-off the Germans. On the sixth day, however, it was the machine gunners who helped repel the successive waves of German troops.

Pvt. Frank R. Stevens, Company C, of Lynchburg, Virginia, who manned one of the .30 caliber light machine guns on the defensive perimeter, mentioned:

Each day a few Germans would work their way up and we would cut them down with rifle fire...(on the sixth day) we all woke up fighting and went to sleep fighting. When we were not shooting, we were tossing grenades.

Company D Gunner, Sgt. Jack Wilson added:

Unlike the .30 "light" machine guns, the 1917 Type .30 caliber water-cooled “heavy” machine gun had the capability to fire single shot or burst. I would fire single shot so I would not let the enemy know he was facing a machine gun. When Jerry committed to assault my position, I let him have burst after burst.

On the 29th the 405th was right on-target. Two supply missions were flown. The first “show” took off at 1005 and was over the drop zone by 1045. Flight conditions over the drop zone were CAVU (ceiling and visibility unlimited). Fifteen planes dropped their tanks laden with critically needed medical supplies, plasma and ammunition. Major John W. Leonard reported 22 landed inside the drop zone, 4 landed 50 yards west, 2 landed 100 yards west, 2 landed 2,000 yards west. The final supply mission took off at 1600 and arrived over the drop zone V-345573. Seven bundles of supplies fell in the drop zone, one bundle fell off in flight, 2 miles west of Bruyères.

Susumu Ito, Forward Artillery Observer with Company I, 442nd during the breakthrough, recalls seeing the red parachutes on the ground in the Lost Battalion area that had been used to drop the medical supplies. He fashioned a red neckerchief out of the parachute material.

As the supplies started to fall in the American zone they were retrieved and stockpiled. Acting commander Martin Higgins Jr., recalled the air-drop scene:

It was like something you would see in the movies, shells falling with food, planes zooming and dropping parachutes, and belly tanks loaded with supplies -- it was really something. Most of the men cried like kids. You just can't put into words how we felt. I ordered all the food brought to one point for a breakdown and equal distribution. And not one man stopped to eat anything. They brought the food, piled it up, and looked at it. It was the strongest discipline I ever saw. Some of the men had to shoot their way to the rations as they landed near the Jerries who tried to grab them first. We had the same sort of trouble at the water hole. Jerry placed snipers there.

The supplies dropped by the 405th arrived in the nick of time.

1st Sergeant William Bandorick, of Company A, remembered:

The men almost cried when the planes came over and dropped food

Staff Sergeant James Lohman, of Company B, Owensboro, Kentucky recalled:

One pilot dropped food right on target, we were all shouting give that guy a Congressional medal.

One flight of the 405th surprised German troops when they overshot the drop zone. The Jabos strafed and bombed enemy troops seen in a clearing observing the drop. The flight inflicted heavy casualties.

Repeated German infantry assaults pounded the Lost Battalion revealing their great numerical advantage. Each was repelled. The advancing 442nd noted the woods around the encircled battalion were full of dead German troops. The last message of 29 October Lt. Higgins sent to HQ was: “Not trying to beg-off, but situation here gets worse.”

The 442nd RCT point of view to rescue the Lost Battalion

On October 29 (the Lost Battalion was down to three rounds per man by the morning of October 29, prior to the ammo drop by the 405th Fighter Squadron), the regiment jumped off again, cleared one knoll, and ran into the enemy's main defensive position thrown astride the ridge where it was so narrow that maneuver was impossible. Any attack was hopelessly canalized into a direct frontal assault. In the meantime, word had come to the battalion command posts that the situation of the "Lost Battalion" was becoming desperate.

Relief must be effected immediately. Consequently, a position that would normally have taken two days to reduce had to be reduced at once.

At the time of the attack, the 3rd Btl was directly under the enemy positions. The 100th had dropped back to the right rear of the 3rd Btl and was not in a position to attack, due to the narrow

conformation of the ridge. The commanding officer of the 3rd Btl, Lieutenant Colonel Alfred A. Pursall, therefore, elected first to turn the enemy's right flank, but the bluff there was so steep

that the men could not maneuver or move quickly. The enemy easily turned back the thrust.

While the men regrouped, a platoon of tanks came up; supported by direct fire from the 75s, the troops were able to advance some distance in an attempt at infiltration before they were pinned

down by the enemy's (Grenadier Rgt 933) relentless small arms and mortar fire. There they remained, unable to advance, unable to turn back; they could look for no other support than that which

they already had. Here was a situation in which battle craft and the weight of supporting fires were worse than useless. All weapons of modern warfare were available but could not be effectively

employed.

There was one chance left. The Battalion took it. As the word to fix bayonets came down the line, I and K Companies moved forward in the assault, firing from the hip and charged up "Banzai Hill".

Men fell; others took their places. The dead lay where they had fallen, inches from enemy holes, over enemy gun barrels, inside enemy dugouts. The remnants of the enemy force that had so

confidently held the positions a short 30 minutes before threw down its arms and fled. For once, there was no counterattack, only the interminable artillery.

In a surprise move three thousand yards to the left rear, the 2nd Btl, led by Lieutenant Colonel James M. Hanley, had taken an important hill, which the enemy had neglected to secure in

sufficient strength. The 2nd Btl reached the top of the hill and stormed down on the unwary Germans. The hill fell and the battalion left a hundred enemy dead behind them, taking 55 prisoners.

This was a fitting climax equally as long and hard as that which had occupied the other two battalions.

The photo shows a telephone wire support in the perimeter of the Lost Battalion.

October 30, 1944 - The Final Day

Lt. Higgins admired 36th Infantry Division commander Major General John Dahlquist's aggressive fighting style. Dahlquist was the only officer from Division Lt. Higgins ever recalled seeing at the front observing his troops in action. On Monday morning, 30 October, General Dahlquist ignored the prime military axiom that dictates one never splits his forces in the face of superior numbers. It was a matter of numbers. General Dahlquist ordered Lieutenant Higgins to split his force, leaving the weapons platoon with the wounded and prisoners, while the rest of the men fought their way back to the advancing 442nd RCT.

Higgins radioed he had twenty-two liter cases, eleven trench foot cases, ten walking wounded, and strong German patrols with automatic weapons probing his perimeter. Including the 43 MIA and 4 KIA this left Lt. Higgins with 180 combat effectives. Pondering his options, Higgins also had numbers to consider. If he subtracted an additional 44 men from his force to carry litters that further reduced the number to 136 combat effectives. So, retreat was not an option. Taking the wounded with them was not an option. Leaving the wounded behind was not an option.

Leaving the weapons platoon with the wounded would leave Lt. Higgins with only 170 men to fend-off a superior German force while moving through territory known to have been mined by the Germans. To leave the weapons platoon with the wounded would most likely relegate those who stayed behind to death or capture.

This greatly complicated the retrograde action ordered by Dahlquist, who, upon learning this information, again ordered Higgins to move his men. Meanwhile, German forays into the perimeter were being met and dispersed by artillery fire-missions from the 131st FA, and D Co.’s heavy machine guns. Much like the “Lost Battalion” of WWI, by standing their ground, the remnants of 1st Battalion 141st Regiment, too, had created a salient in the German line. The Germans laid down smoke. The Lost Battalion braced for what would surely be a major assault. However, the assault never came. The smoke laid down was not to obscure the German advance, but rather to cover their retreat.

Late in the afternoon, Weapons platoon "topkick," T/Sgt. Eddie Guy, of New York City, who commanded Able Company's .30 caliber "light" machine gun, observed some movement in front of his position. The "movement" was T/Sgt Tak Senzaki leading the advance patrol of I Company, with Private Matsuji "Mutt" Sakumoto, of the 3/442, on point, as scout.

Private Mutt Sakumoto advanced toward T/Sgt. Guy's position on the defensive perimeter. Sakumoto nonchalantly asked Sgt. Guy: "Do you guys need any cigarettes?" The 442nd had broken through to the "Lost Battalion." Lt. Blonder sent the message at 1600hrs:

Patrol from 442 here. Tell them that we love them!

The 442nd RCT point of view to rescue the Lost Battalion

On October 30, although the back of the German resistance had

been broken and infantry action was sporadic, the artillery kept pouring in. Finally, at 1500 hours that day, with the 3rd and 100th Battalions moving as much abreast as possible, a patrol from I

Company, led by Technical Sergeant Takeo Senzaki, made contact with the "Lost Battalion." Shortly thereafter, the main bodies linked up. The impossible had been accomplished. After the attack,

Companies K, L, and I were down to less than 20 men standing each, out of 200 at full strength. Only a handful of Nisei's that were still able to walk made contact with the Lost Battalion. Of 275

men cut off six days earlier, only 211 remained. "Saying we were thrilled is an understatement," commented Lt. Marty Higgins, veteran of A Company, 1st Battalion, 141st "Alamo" Rgt, who was in

command of the Lost Battalion.

When the German Grenadier Rgt 933 was withdrawn after surrounding the "Lost Battalion" and fighting the 442nd RCT, only eighty men remained of a force that had nearly three thousand men three

months earlier.

After the Siege

The saga of the "Lost Battalion," of World War II, came to a close. Of the 270 men of the "Lost Battalion," some 211 answered muster on the morning of Monday, 30 October. The unit strength by company was Co. A: 45 men, Co B: 71 men, Co C: 81 men and Co D: 14 men. The wounded were sent to the rear. The rest of the "Lost Battalion spent one more night in their foxholes. The next morning, Tuesday, some 180 men of the Lost Battalion walked out of the Trapin de Saules. They had inflicted heavy losses on the enemy and took four prisoners. History had repeated itself. The stubborn and gallant defense mounted by the "Lost Battalion," made possible, by the re-supply efforts of the 405th Fighter Squadron, coupled with the valiant efforts of the 100/442nd RCT, forced the Germans to retreat. The ground so doggedly held by the "Lost Battalion" served as a springboard for the subsequent assault on St. Die and the advance to the Alsatian Plain.

"Alamo Company," Co. A, 1st Battalion, 141st Regt., 36th Infantry, traces it's heritage back to Company A, First Regiment, Texas Volunteer Guard, organized in early 1836 at Washington-on-the-Brazos, as the Washington Guards. Elements of the Texas Militia served with Colonel William Travis at the Alamo. "Alamo Company," had lived up to its name.

Due to the vicissitudes of war, the players in the drama that unfolded in the Vosges Mountains went their separate ways. Among the rifle companies of the 141st Infantry, the average strength now numbered 83 men or less. The men of the "Lost Battalion" were sent into a rear area bivouac near Lepanges for a brief rest and replacement training. Three days later, they would be back in the line.

Colin Wills, a BBC war correspondent, who will be remembered for his stirring coverage of the D-Day landings (“This is the day, and this is the hour”), interviewed Lt. Higgins. The interview was included in the BBC program "Radio Newsreel" and was broadcast from London to New York. It was then re-broadcast to the rest of America from the New York studio of the BBC on 5 November 1944.

NBC war correspondent Corporal Jay McMullen interviewed Lt. Higgins and Sgt. Kripisch for a segment of the popular news program "Army Hour." NBC's "Army Hour," the brainchild of veteran producer Wyllis Oswald Cooper, was broadcast every Sunday afternoon between 3:30 P.M. to 4:30 PM from NBC's studio 8-H in New York The popular show had over 3 million listeners.

Reporters from Yank, Stars & Stripes, and the major news services also interviewed Lt. Higgins and members of the Lost Battalion. The story went nation-wide. During November 1944, the United Newsreel Corporation's newsreel film about the trapped Battalion played in movie theatres across the country.

The U.S. Seventh Army claimed the honor of being the only army in history to defeat a force defending the Vosges Mountains.

On 1 November 1944, the XII Tactical Air Command (TAC) was transferred from the Ninth to the First Tactical Air Force. The 371st Fighter Group moved to Tantonville, Nancy, Metz; and then parted company with the Seventh Army.

The 100/442 RCT suffered 54 KIA and 156 wounded in the breakthrough effort to reach the "Lost Battalion." During the month of October the 100/442nd RCT suffered 639 casualties.

All in all, 161 of the 2,943 men entering the engagement in the forest had been killed, 43 were missing, and about 2,000 were wounded.

There are three main Allied elements to the Lost Battalion

saga of WWII:

1.) 1/141, 36th ID

2.) 100th 442nd Regimental Combat Team - comprised of Japanese-Americans with Caucasian officers.

3.) the 405th Fighter Squadron/ 371st Fighter Group, 70th Wing, 9th U.S. Air Force; based at Dole/Tavaux.

Porter's Rock

"......The group I was with ran into a German soldier chopping trees who didn't see us, but no one felt brave and we did nothing about him. Our small group arrived at the I company CP on the rocky hilltop while the company was still enroute from wherever they had been. While waiting for I Company and its captain, we stood around chatting until the 88mm shell hit a tree amoung us. Only one shell ? Yes I wonder why there weren't many ?......"

That happened on October 31st 1944... - Joe Parks, was 1st Lieutenant 3rd bn 141st, and it was his first day of fight. For a long time, he was remembering that day... for all his life in fact..... One day, with his help, my friend Gerome discoverd the Rock ! Sending photos, Joe recognized it.... Several years later, Gerome and others decided to pay tribute to the radioman, Walter Porter, 131st FAB in naming the rock "La roche Porter" (Text taken from FB site Vosges History Guide).

Martin J. Higgins Silver Star citation for action during the Lost Battalion engagement dated 1 July 1945:

Martin J. Higgins, 01030984, Captain (then First Lieutenant) 141st Infantry Regiment, for gallantry in action from 23 to 31 October 1944 in France. When the 1st Battalion was completely surrounded by hostile troops and isolated from other friendly units, Lieutenant Higgins assumed command of the organization and, despite heavy artillery and mortar fire, skillfully directed his men in establishing a perimeter defense. Although the troops were without food and water and were subjected to a series of strong German attacks, Lieutenant Higgins worked tirelessly and courageously to maintain the morale of his men and, bravely exposing himself to hostile fire, directed elements of the battalion in repelling the attacks with heavy losses to the enemy. After five and a half days of continuous effort he succeeded in arranging for supplies to be dropped by planes; and when some of the supplies landed in hostile territory, he personally conducted patrols to recover them. During this trying period his courageous and resourceful leadership inspired his men and kept them well-organized and encouraged until help arrived. Entered the service from Jersey City, New Jersey.

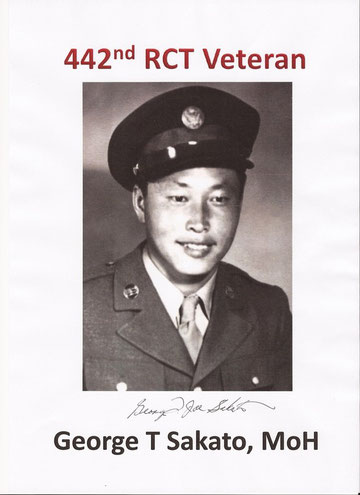

Three Congressional Medals of Honor were awarded for heroism during the Lost Battalion breakthrough effort. Private Barney Hajiro, Company I, 3rd Battalion, 442nd RCT, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, which was later upgraded to the Congressional Medal of Honor. Private George Sakato, Company E, 2nd Battalion, 442 RCT, earned the Distinguished Service Cross, which was later upgraded to the Congressional Medal of Honor. Also, Technician Fifth Grade James Okubo, a medic would earn a Silver Star for “Gallantry in Action,” which was later up graded to a Congressional Medal of Honor. On 18 November they were detached from the 36th and assigned to duty in Italy. In a series of brilliant maneuvers the 100/442nd RCT would reduce the Gothic Line and secure the Po Valley.

Years later, on 21 October 1963, Texas Governor John Connolly would proclaim the men of the 442nd RCT "Honorary Texans."

The 141st Regiment, 36th INF Division moved ever eastward, deeper into the Vosges, and ultimately across the Rhine. Correspondent Jay McMullen signed off from his interview of the Lost Battalion with a prophetic admonition for the Germans: "The Lost Battalion isn't lost anymore and plenty of Jerries will find that out before this war is finished."

Battle Honors: Unit Awards / Presidential Unit Citations (Army)

The 442nd Regimental Combat Team was awarded seven Distinguished Unit Citations (name changed to Presidential Unit Citations in 1966). This is the highest award that a unit can earn. For ist heroic actions in the French Vosges Mountains, the 442nd RCT earned no less than 5 Presidential Unit Citations (marked Red below).

100th Infantry Battalion (Separate)

War Department General Orders 66, 15 August 1944:

The 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate) is cited for outstanding performance of duty in action on 26 and 27 June 1944, in the vicinity or Belvedere and Sassetta,

Italy.

100th Battalion, 442nd Regimental Team

War Department General Orders 78, 12 September 1945:

The 100th Battalion, 442nd Regimental Team, is cited for outstanding accomplishment in combat during the period 15 to 30 October 1944, near Bruyeres, Biffontaine, and in the Foret Domaniale de

Champ, France.

2nd Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team

War Department General Orders 83, 6 August 1946:

The

2nd Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team, is cited for outstanding performance of duty in action on 19 October 1944 near Bruyeres, France, on 28 and 29 October 1944 near Biffontaine, France,

and from 6 to 10 April 1945, near Massa, Italy.

Companies F and L, 442nd Regimental Combat Team

War Department General Orders 14, 4 March 1945:

Companies F and L, 442nd Regimental Combat Team, are cited for outstanding performance of duty in action on 21 October 1944, in the vicinity of Belmont, France.

3rd Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team

War Department General Orders 68, 14 August

1945:

The 3rd Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team, is cited for outstanding accomplishment in combat during the period 27 to 30 October 1944, near Biffontaine,

France.

232nd Engineer Combat Company (then attached to the 111th Engineer Combat Battalion)

War Department General Orders 56, 17 June 1946:

111th Engineer Combat Battalion with 232nd Engineer Combat Company (attached), for heroism, esprit de corps, and extraordinary achievement in combat from 23 October

to 11 November 1944 near Bruyeres, France.

442nd Regimental Combat Team (less the 2nd Battalion and the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion)

War Department General Orders 34, 10 April 1946, as amended by War Department General Orders 106, 20 September 1946:

The 442nd Regimental Combat Team (less the 2d Battalion and the 522 Field Artillery Battalion) composed of the following elements: 442nd Infantry Regiment, 232nd

Combat Engineer Company, is cited for outstanding accomplishment in combat for the period 5 to 14 April 1945 in the vicinity of Serravezza, Carrara, and Fosdinovo, Italy.

SGT ROCK - The Lost Battalion - by Billy Tucci

Thanks to my friend Billy Tucci, I got this awesome comic which is telling the story of the 141st Infantry of the 36th Texas Division. This outfit got surrounded by the Germans and fought for their lives until it was rescued by the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Billy Tucci tells a saga of Americans under fire in this tale of courage, bravery and the heroes living among us. It's the story to give the 442nd RCT the credit they deserve.

George T. Sakato - Medal of Honor

Private Sakato's official Medal of Honor citation

reads:

Private George T. Sakato distinguished himself by extraordinary heroism in action on 29 October 1944, on hill 617 in the vicinity of Biffontaine, France. After his platoon had virtually destroyed two enemy defense lines, during which he personally killed five enemy soldiers and captured four, his unit was pinned down by heavy enemy fire. Disregarding the enemy fire, Private Sakato made a one-man rush that encouraged his platoon to charge and destroy the enemy strongpoint. While his platoon was reorganizing, he proved to be the inspiration of his squad in halting a counter-attack on the left flank during which his squad leader was killed. Taking charge of the squad, he continued his relentless tactics, using an enemy rifle and P-38 pistol to stop an organized enemy attack. During this entire action, he killed 12 and wounded two, personally captured four and assisted his platoon in taking 34 prisoners. By continuously ignoring enemy fire, and by his gallant courage and fighting spirit, he turned impending defeat into victory and helped his platoon complete its mission. Private Sakato's extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit on him, his unit, and the United States Army. (Text taken from Wikipedia)

Acknowledgements

I would like the following persons for helping me in this report:

Michael Higgins; son of Captain Martin J. Higgins, CO, ABLE Company, 1st Battalion 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th Infantry Division

Virgil W.Westdale - veteran of the 442nd RCT

George T. Sakato - veteran of the 442nd RCT

Lawson Sakai - veteran of the 442nd RCT

George Kanatani - veteran of the 442nd RCT

Gerome Villain – Tour Guide

Billy Tucci - Comic Artist